Muster Roll Troop I April 30, 1854

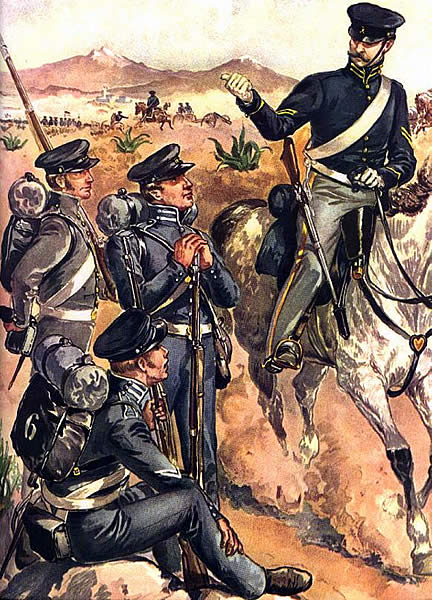

John W. Davidson circa 1875

John W. Davidson circa 1875Captain William Grier, on leave

1st Lt. John W. Davidson, commanding, slightly wounded Cieneguilla

Non-Commissioned Officers

James Batty 1st Sgt. (promoted 1 April 1854) 9 January 1850, Taos, New Mexico

Terr. (See Below.)

Augustus O'Hook Commissary Sgt. 1 August 1851, Rayado, New Mexico, Territory

Benjamin Dempsey Sgt. April 2, 1850, Utica (wounded Cieneguilla 30 March 1854; promoted 1 April 1854.)

Richard Byrnes Sgt. (promoted 1 April 1854) June 12, 1850 NY; wounded Cieneguilla (sgt. major of 1st Cavalry 1856-61; 1st lieutenant 17th Infantry, May 14, 1861; transferred to 5th Cavalry Sept. 21, 1861; Col. 28th Massachhusetts Infantry 18 October 1862; died of wounds received at Cold Harbor 3 June 1864; see Lowe, Five Years a Dragoon (U. Okla 1965), 20-21.

William Gorman Corp., March 20, 1851

Leonard Beckwith Corp. April 22, 1850, Utica

James W. Strowbridge, Corp. (appointed 1 April 1854) from Burlington Vermont, a bricklayer, August 27, 1853, Burgwin, aged 26 years, blue eyes, brown hair, floid complexion and standing 5' 8"; re-enlisted 18 July 1858 at Ft Tejon in Company B; deserted 7 October 1859.

Benjamin Fricke Bugler November 24, 1849, Philadelphia

Henry McGrath Bugler May 18, 1850, Phila. (slightly wounded Cieneguilla)

Byars Jenkins Farrier (appointed 1 April 1854; slightly wounded Cieneguilla)

May 6, 1850 Boston

Privates

John H. Arest March 10, 1852, Cantonment Burgwin

Joseph Baitsell March 20, 1850, Philadelphia (wounded Cieneguilla)

Patrick Boyle February 1, 1851, Rochester (Musketoon $11.00; Colt revolver

$25.00; pistol flask $1.00) in confinement

James Bronson November 22, 1849 Rochester (severely wounded Cieneguilla) aka

James Bennett, 1849 (deserted from B company in March of 1856; studied

medicine and became assistant surgeon 6th and 13th NY Heavy

Artillery during Civil War; died 14 Jan. 1909 in Plattsburg, NY).

Ralph Burnham April 7, 1853, Baltimore (extra clothing $12.60)

Herman Clark March 27, 1851 Baltimore

William F. Coder May 3, 1853 Philadelphia (DD hospital)

Charles Crout January 22, 1851 Baltimore (severely bruised Cieneguilla)

Owen Curtis February 18, 1851 Boston (slightly wounded Cieneguilla)

Francis Daykin March 27, 1851, Baltimore (sick)

Joseph Dowd April 1, 1850, Utica (slightly wounded Cieneguilla)

Geroge Erskine November 12, 1849, Philadelphia

Robert Evans January 3, 1853

William Fullerton March 5, 1851, Boston

Henry Griffiths July 1, 1851, Rayado

Robert Haight November 20, 1850, Rochester

Samuel Haines May 24, 1850, Philadelphia (hospital attendant)

George Howlett August 3, 1849, Taos (hospital attendant)

Jno F. Hutchinson 1 November 1851, Ft. Union, a bookbinder by trade, 3 July 1854, obtained writ of habeas corpus from the territorial court releasing him from service on ground that he had be illegally enlisted due to his being married at time of enlistment. Previous service with Co. E, 7th Inf. discharged 15 December 1849.

Michael Lawless December 4, 1849, Boston

Bradford Lewis September 6, 1850, Rochester

Edward Maher January 21, 1851, Boston

James Mason December 3, 1849, Philadelphia

Frederick Miller February 26, 1850, Philadelphia (severely wounded Cieneguilla)

Henry Miller December 28, 1852, Philadelphia (severely wounded Cineguilla

DD teamster)

Ferd. Newhand March 26, 1851, Baltimore (DD teamster)

Richard Oliver October 21, 1852, New York

Jacob Plethe May 18, 1849, Philadelphia

Jamers Powell March 26, 1851, Baltimore (DD carpenter)

John Shea February 27, 1851, Boston

Shirer, George March 24, 1850, Boston (extra clothing $3.53)

Sam Sommerville March 1, 1851, Philadelphia (slightly wounded Cieneguilla)

Hiram Stevens March 5, 1851, Boston

Peter Sullivan January 7, 1850, NY (wounded Cien. and later died of wounds)

Robert Wert March 14, 1850, NY (extra clothing $.66)

David Wallace March 20, 1850, Philadelphia (extra clothering $5.70)

Horatio W. Weed February 1, 1854, Burgwin

Peter Weldon March 3, 1851, Philadelphia (wounded Cieneguilla)

John Wilson November 3, 1852, Baltimore

KIA

1st Sgt. Wm Holbrook July 1, 1853, Burgwin

Sgt. Wm Kent July 19, 1851, Burgwin

Farrier Reuben Snell March 25, 1851, Philadelphia ($208.37½ found on body)

John Bradley December 14, 1852, NY

Augustus Brenker March 31, 1851, Philadelphia

John Dale March 19, 1851, Baltimore

Wm Driscole June 22, 1851, Boston

Thomas Gibbins April 15, 1850, Baltimore

Louis Humbert December 2, 1850, NY

William Null March 31, Philadelphia (extra clothing $6.07)

Reuben Pease March 21, 1850, Utica

Gordon R. Rennie March 26, 1849, Baltimore

Charles F. Rottger February 15, 1851, NY

Ryan

1st Sgt. John Batty enlisted in the Dragoons in 1840. While in his fifth tour of duty, as his company prepared to march East to fight in the Civil War, this veteran of 21 years of hard service died of a fever in Los Angeles in August of 1861.

MUSTER ROLL Troop F April 30, 1854 (Note that F Company detachment of 15 men suffered 100% casualties at Cieneguilla.)

Bvt. Major and Captain Philip H. Thompson, commanding

Non Commissioned Officers

1st Sgt. Thomas Fitzsimmons 20 January 1851, NY

Sgt. C. Frank Clarke (former sgt. major; born in Suffolk County, England; enlisted 1 October 1849, Jefferson Barracks; was on detached service carrying dispatches from Santa Fe at time of battle; discharged 1 October 1854; later captain, company I, 6th Kansas Mounted Volunteers, died 10 December 1862, Memphis Tennessee.)

Sgt. John Horan 1 November 1849, Boston

Sgt. John Cameron 22 October 1849, NY (in arrest; discharged 22 October 1854)

Corp. Jno K. Davis 23 November 1850, Boston (slightly wounded

Cieneguilla) (re-enlisted)

Corp. Hugh Cameron 4 Mar 1851, NY

Corp. Francis Arthur 20 August 1853, Ft. Massassusetts (horse blanket

$2.50)

Corp. Charles H. Hanish 21 August 1853, Ft. Massassusetts

Bugler James Clark 17 March 1853, Philadelphia

Farrier Edward O'Meara 17 February 1851, Buffalo

Privates

Robert W. Allen 20 March, 1851, Las Vegas, NM (3d enlistment)

John Armstrong 20 May 1852, Baltimore (in confinement Burguin; discharged 4 October 1854)

Jerome Bates 27 October 1849, Boston (sick wounded

Cieneguilla)(re-enlisted)

James Buck 27 March 1851, Las Vegas (sick severely wounded

Cieneguilla)(re-enlisted)

Neil Brewer 15 October 1852, Ft. Massassusetts (spurs & straps $1.10)

Augustus Bradley 12 March 1853, Philadelphia (spurs and strap $1.10; deserted 1 October 1854)

Louis Crosbie 15 September 1849 NY

William Carroll 18 March 1851, Philadelphia (spurs and straps $1.10)

John Cooper 28 March 1851, Taos (re-enlisted)

William Cassidy 9 February 1852, Taos (re-enlisted)

George W. Davis 15 December 1851, Las Vegas

Benjamin Engle 8 November 1849, Rochester

Theodore Fricke 27 January 1851, Las Vegas (re-enlisted)

Michael Flood 15 March 1851, NY (severely wounded Cieneguilla)

Joseph Fox 26 April 1852, Baltimore (sick)

Jacob Fullmer 17 March 1851, Phila (in confinement, Jefferson Bks; dropped from the rolls on 19 December 1854 "in consequence of his being a felon & not having heard of him since June of 1853."

John Garrett 8 November 1849, Baltimore

Willaim Grieseman 7 October 1852, Galisto, NM (re-enlisted)

John Harper 7 October 1851, Las Vegas (re-enlisted)

William Gray 12 October 1852, Galisto (re-enlisted)

Henry Jacobs 27 February 1851, Baltimore (held under charges)

Joseph Johnson 22 May 1852, Columbus (Lt. Love)

Henry Kirchner 1 March 1852, NY

John Keebler 2 February 1852, Ft. Leavenworth (Revolver $25.00)

Augustus Kraus 21 April 1852, NY

Daniel McFarlan 17 April 1852 NY

Thomas Meecham 20 October 1852, Philadelphia

Jeremiah Mahoney 19 January 1851, Boston (severely wounded Cieneguilla)

Patrick Madden 20 May 1852, Baltimore

Benjamin Platiner 1 March 1853, Philadelphia

Aaron D. Stevens 1 April 1851, NY

Jeremiah Sullivan 20 November 1852 NY (severely wounded Cieneguilla;

prisoner under charges)

Jim Vanderlen 23 Nov. 1849, Ft Smith (Colt Revolver $25.00 teamster)

Philip Welsh 21 February 1852, Alburqueque (old soldier bounty)

Robert Walsh 26 March 1851, Las Vegas (old soldier bounty)

Frank Winder 25 February 1851, Baltimore (slightly wounded

Cieneguilla)

George Winache 1 November 1849, Ft, Scott

Aaron Williams 26 November, 1853, Taos

KIA

Thomas Awant 14 March 1853 NY

Martin Bowditch 11 March 1849, Boston

Geo. W. Brieswood 25 February 1852, Baltimore

William Fell, 18 Feb 1853, Philadelphia (wounded Cieneguilla, died 6 April 1854)

Willaim Mitchell 18 February 1853, Philadelphia

Thomas Higgins 14 Dec. 1852 NY

Henry Kimble 19 February 1851, NY

Alexander McDonald 23 October 1849, NY

Anton Schmontz 25 February 1851 Baltimore

Discharged Disability

Charles Hopping 6 May 1852, Ft. Union

Desertion

Bugler James Cook 20 March 1849, Baltimore (deserted April 5, 1854; horse, blanket,

equipage, Sharps, sabre and belt, cartridge box)

Pvt. Joseph Branson 12 February 1852, Gallisto, NM (re-enlisted) (deserted April 5, 1854,

Musketoon, Grimsley saddle, cartridge box and sabre belt)

Patrick McConnel 22 June 1852, Baltimore (deserted April 5, 1854, horse and

equipage, sling and swivel, Mississippi Rifle, flask, sabre.)

James Moss 18 January 1853, Philadelphia (deserted April 17th 1854, horse

and equipage, Colt revolver, pommel holster, cartridge box

Musketoon, sling & swivel.)

Following the battle, Lt. David Bell, 2d Dragoons, wrote a letter to a brother officer that was highly critical of Lt. Davidson. Davidson requested and was granted a Court of Inquiry to investigate Bell's accusations. Col. E. V. Sumner, Bell's commanding officer at Ft. leavenworth, refused to allow Bell to attend the hearing. Bell wrote to Gen. Winfield Scott and obtained permission to attend. Unfortunately, the hearing had concluded by the time that the information reached the Department of New Mexico and Bell was unable to attend the hearing. Below is Bell's letter to General Scott.

Lt. David Bell

Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas Territory

March 8, 1856

Colonel:

I have been informed that charges have been preferred against me by Capt. John W. Davidson, 1st. Drags, for certain statements contained in a letter, written by me, and that the Genl. commanding the Army had decided thereon, that previous to a trial by a Court Martial, a Court of Inquiry must be assembled to investigate the circumstances upon which the allegations contained in my letter are based. I have also learned that a Court of Inquiry has been asked for by Capt. D. and that it has been granted him. In case this Court is ordered to assemble, I would respectfully request to be ordered to be the point where the Court may assemble. I make this request for the following reasons:

I. I am the only person cognizant of some of the circumstances, asserted in the letter in question, and other statements can only be substantiated by evidence of which I am in possession, and which is not known to any person in the Dept. of New Mexico otherwise than by my written statements. It certainly cannot conduce to the ends of either truth or justice to assemble a Court of Inquiry to investigate circumstances so greatly affecting the reputation of an officer, while he is debarred the privilege of defending himself against allegations made against him.

II. An investigation by a Court of Inquiry, with but a hearing upon the side of an accuser, would undoubtedly result in a trial by Court Martial, and I desire to avoid the unremediable reputation (however unmerited) of an officer who has been tried by Court Martial.

I hope when the delicacy of my position is considered, I will be granted my request.

I am, Colonel,

Your Very respy, Your Obt. Servt.

D. Bell, 1st Cavalry

Endorsement:

March 24, 1856

If a Court of Inquiry has been ordered as within stated, it is proper Lt. Bell should be in attendance and the Genl. Comdg. in New Mexico will cause him to be summoned, provided the Court have not adjourned sine die, and been dissolved prior to the receipt hereof by command of Bt. Lt. Gen. Scott . L. Thomas, Adj. Genl.

(