Kugler:

Die US KavallerieCopyright 2006, New Mexico Historical Review

During a lull in the fighting at Santa Cruz de Rosales, James Glasgow had taken a brief nap. He was awaken by the screams of a wounded man who was having his leg sawed away by an army surgeon. A short distance away he saw hospital attendants “dressing the stump of another’s which had just been cut off. I didn’t feel sleepy again for some time. War is an ugly business and I could not help thinking when it was all over, that this thing of people’s killing each other is the greatest nonsense extant.” The date was March 16, 1848—the Mexican-American war had officially ended six-weeks prior, but this battle would continue.

On 16th March 1847, a squadron composed of Companies B, I, and G of the 1st Dragoons, Major Benjamin Beall commanding, and a regiment of the 3d Missouri Mounted Rifles, under the joint command of General Sterling Price, participated in an attack upon the Mexican town of Santa Cruz de Rosales. The battle is remarkable in three respects. First, Company B acted as a light artillery battery, secondly, the battle took place over a month after the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo had been signed (2 February 1848), and third, following the battle, the Missouri troops engaged in the "Cow Pens" massacre of Mexican soldiers. What follows is a remarkable tale of a battle that seldom receives, at best, not much more than a sentence or two in most accounts of the Mexican-American War.

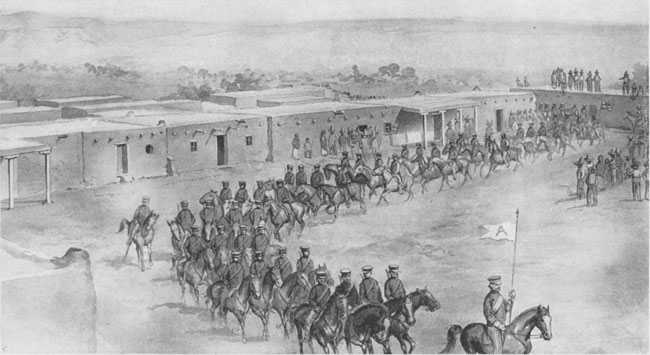

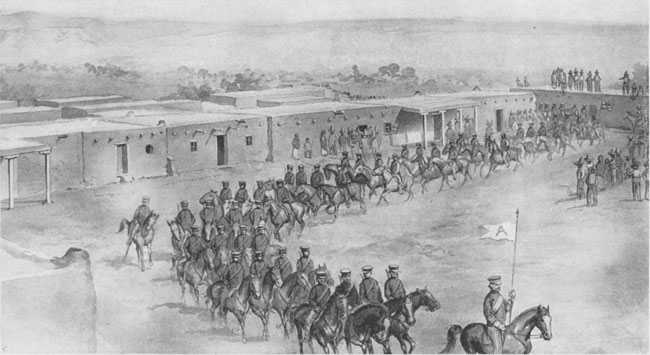

August 6, 1847: The New Mexico sun beat down mercilessly upon the column of seventy Dragoons in dusty blue shirts as they entered Santa Fe. A light breeze caused the red and white swallow tailed guidon to lutter. At the head of the column the young lieutenant smartly saluted the provost guard. After nearly a year back east on recruiting duty, Lt. John Love was back in Santa Fe with his recruits. General Winfield Scott's army was at the gates of Mexico City, and Lt. Love hoped that there would be an opportunity for him to gain a Captain's brevet before the war ended.

The detachment had been on the Santa Fe Trail since June 5th. Sent west as members of newly reconstituted B Company of the First United States Dragoons they had escorted Army Paymaster Bodine's wagons. Most of these Missouri and Indiana farmboys had been in the army for less than six months but had already “seen the elephant,” having been attacked, outridden and defeated by Comanches on the plains of Western Kansas Territory five weeks earlier. Five of their number were behind in unmarked graves along the trail, six others were wounded in that attack. (See Wild West: June, 2004.)

Well-mounted on big-boned, black sorrells, the recruits hardly appeared soldierly, neither in bearing nor uniform. Despite the cursing of the sergeants, many of the riders had difficulty maintaing a smart column of twos as they clattered past the governor's palace. “Right into line,” came the command. The troopers wheeled their restive mounts and, with some difficulty, the column eventually fomed into a ragged line. The lieutenant shouted, “prepare to dismount, draw carbines, dismount.”

What these recruit lacked in training the recruits made up in enthuasism and patriotism. Lt. Leonadis Jenkins trained a detachment of these men while they were at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri and wrote Lt. Love, “I have 13 men and in a few days think I will make it up to 20—as good men as ever enlisted. They get along rapidly in their drill on foot and if I only had a few horses and saddles could have them pretty well instructed by the time that you are ready to receive them.” Unfortunately, these good men had been rushed into the war with virtually no training in what the 1841 Army Manual called, “School of Trooper, Mounted,” otherwise known as horsemanship. Quite simply, they were not ready to be thrown into the fray as a mounted unit.

But army headquarters had special plans for the unsteady horsemen of Company B. Believing there was no time to train them to fight as Dragoons, Company B would be transformed into a field artillery battery. On August 16, 1847, Lt. Love drew six cannon from military stores in Santa Fe: two powerful 24-pounder howitzers, one 12-pounder mountain howitzer, and 3 Mexican artillery pieces. One of the these latter cannons was a six-pounder, seized by Mexican troops from an ill-fated 1843 expedition of the Republic of Texas sent west to conquer Santa Fe and then captured by General Kearney forces when they took possession of Santa Fe in 1846.

On September 7, 1847, Company B was ordered to Albuquerque, where it encamped with veteran Dragoon Companies G and I. While their artillery horses and mules grazed peacefully under the stand of cottonwood along the grassy banks of the meandering Rio Grande, the men of B Company drilled as artillerists.

A brief word about Mexican War era field artillery is in order. The terms "24-pounder" and "6-pounder" refer to the weight of solid shot fired out of the cannons. Cannons of this period could also fire explosive spherical case shot: a hollow ball filled with small pellets, a bursting charge, and timing fuse. For firing at enemy troops at under 400 yards, the guns fired canister: a tin can filled with iron balls that, when fired, turned the weapon into a massive shot gun. Howitzers were designed to lob larger caliber projectiles at enemy positions. In order to improve their maneuverability, these pieces employed barrels that were shorter and lighter than those of other types of cannons.

The training of a field artillery unit was the most difficult of the three branches of combat arms. Whether a artilleryman be a driver or cannoneer, he was trained to load and fire the piece, cut fuses of shells, mount and dismount the piece and limber, harness and drive a team, or replace a damaged wheel. Once these multifaceted skills had been learned, the battery of six horse-drawn cannon and accompanying artillery limbers would engage in field maneuvers.

On September 14, 1847, General Winfield Scott captured Mexico City. The war now diminished to a few scattered skirmishes, the diplomats were taking and an end to hostilities was in sight. But on February 4, 1848, a report reached Santa Fe that a Mexican army of 3,000 men was marching north from Chihuahua with the objective of re-capturing Santa Fe. The report would prove to be inaccurate, but for General Sterling Price, in command of all United States troops in the theater and sensing his chance at glory to be fast slipping, had other ideas. A former member of Congress, Sterling Price had resigned his seat when the Mexican War broke out and raised a regiment of Missouri volunteers. Sent to command a garrison to protect New Mexico, now a backwater of the war, his troops had seen only limited action against Navajo raiders and Mexican insurgents. Finally and long last, here was a chance for the politician-turned-general to grab some last-minute glory on the field of battle.

General Price decided to move the bulk of his forces down the Rio Grande Valley so that they would be nearer the enemy. He promptly issued orders for the three Dragoon companies at Albuquerque to march post-haste to El Paso del Norte to reinforce the garrison of Missouri volunteers stationed there.

Hearing news of the impending campaign, veteran Sergeant Benjamin Bishop, although still suffering from serious wounds he received during the fight with the Comanche in June, left a hospital bed in Santa Fe to join his company. Trooper Lewis Dunbar, a sturdy 5'5" blacksmith from Johnson, Indiana, although sentenced to a term of six months on hard labor for having deserted his sentry post, was released from the guardhouse so that he might drive the company's ammunition wagon.

On February 8th, General Price, left Santa Fe, and with an escort company of the Missouri Horse regiment, rode 340 miles to join his command in El Paso. Upon arrival, General Price received orders from Adjutant General Roger Jones directing him to stay put in El Paso and, if possible, send five or six hundred of his mounted troops west to reinforce the under strength forces that were occupying California.

The inhabitants of the Mexican state Chihuahua viewed with apprehension the steady build up of American forces in El Paso. The January 19, 1848 edition of the Faro, a Chihuahua newspaper, reassured the populace by reporting the Yanquis lacked sufficient supplies and provisions to invade. But the troops, however, were not in want of mutton: the Faro also mentioned that rancher Don Ignacio Roquillo had complained of Price’s men having taken 700 of his sheep and not paid him a cent.

The paper was also wrong with regard to troop movements. On February 26th, General Price ordered Major Walker's three mounted companies of the Santa Fe Battalion to ride 90 miles south and occupy the desert town of Carrizal. From this strategic location, Price believed that Major Walker would command the passes on the roads to Chihuahua and could observe the operations of any approaching force. Major Walker dutifully sent out patrols far and wide into the trackless Chihuahuan Desert, rounded up a few Mexican army stragglers, but found no evidence of any organized Mexican force.

Ignoring Walker's intelligence and his orders from the Adjutant General to remain in El Paso, General Price, with four companies of 3d Missouri Horse and two companies of 1st Dragoons, waded the broad Rio Grande and headed south across the wilderness of the Chihuahuan Desert. His objective was Chihuahua, a town of 14,000 residents. As he neared the Rio Sacramento, a Mexican patrol approached under a flag of truce. They gave General Price a note from Mexican Governor General Angel Trias. The dispatch contained surprising news: a peace treaty had been signed on February 2d at Guadalupe Hidalgo, a villa on the outskirts of Mexico City, and a cease fire had been declared.

Not having received any official word of a peace treaty and doubting Trias' representations, the general continued his advance. General Price, although distant from reliable sources of intelligence, should have believed Trias: he was fully aware that Mexico City had been taken five months prior and all major operations in the war had ceased. Furthermore, he was in receipt of orders to not move his forces south of El Paso.

Seeking to avoid bloodshed and having inadequate forces at his disposal, Governor Trias abandoned Chihuahua and with four hundred soldiers and some cannon, retreated south towards Santa Cruz de Rosales. There he expected to have his force reinforced with one hundred National Guard troops, under the command of Lt. Colonel Vicente Sanchez, marching from the State of Durango.

After a rapid march of sixty miles down the highway to Durango, Price caught up with General Trias on March 9. By this time, Trias had reached the shelter provided by the mud-walls of Santa Cruz de Rosales, a small Mexican village. The governor-general again insisted that a peace treaty had been signed and requested an armistice so that a courier might bring a copy of the document. General Price, realizing that he lacked sufficient troops and artillery to carry the town, agreed not to take action for five days.

Both sides honored the five-day armistice, and both generals, in the meantime, called for reinforcements. During the wait, Price’s forces camped in the woods about a mile east of the town. Over one-hundred Mexican troops under the command of Colonel Cayetano Justiani slipped through the Yanqui lines and entered Rosales on March 10th. A few nights later, two hundred more troops of the 2d Battalion of the National Guard entered the town. These reinforcements swelled Trias’ force to over eight hundred men.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Love’s battery was encamped 210 miles north of Santa Cruz de Rosales. On 12 March, he received Price’s orders to support the general in Rosales. Mounting some of his newly minted artillerists on fast traveling sorrels and others on artillery teams, accompanied by three companies of the Third Missouri Horse, he raced to the scene of the siege—covering the distance in three and one-half days, sixty of the miles in the final twenty-four hours. This feat was made even more remarkable in that two of the cannon were heavy howitzers—neither weapon designed to move as light artillery nor to travel in mountainous terrain.

Santa Cruz de Rosales hardly looked appropriate for a bloody siege and massacre. Situated at an elevation of thirty-nine hundred feet, the town sat adjacent to the Rio San Pedro, a clear mountain stream that courses the plain on its northeastern pathway down to the Rio Grande. Surrounded by freshly plowed fields watered by irrigation ditches, the town sat astride the dusty road from Chihuahua to Durango. Spring had arrived early in March 1848. Philip Gooch Ferguson, a Missouri Volunteer, noted in his journal, “The cottonwoods were in full leaf; and the grass quite green; peas and other vegetables in full blossom.”

In 1848, Santa Cruz de Rosales extended for about three-quarters of a mile along the road in a northeast/southwest axis. It was about a quarter mile at its widest point. In the town’s center was a 200 yard-long plaza. On the west side of the plaza sat an imposing and elegant cathedral. Most buildings were low, mud-walled structures with flat roofs.

General Trias's defending force of 804 men was a mixed lot. It primarily consisted of elements of the 2d Battalion of National Guard along with some regular (permanente) artillerymen and cavalry. There was also a detachment of presidiale lancers commanded by Lt. Colonel Vicente Sanchez. Inadequately equipped, even as police force, the black hated, blue-jacketed presidiale lancers guarded and protected Mexico’s northern frontier. The infantry was armed with British Brown Bess muskets--flintlock relics of the Napoleonic era weapons that had an effective range of about seventy-yards.

In order to protect his troops from exposure to artillery and rifle fire, General Trias placed most of his men in the town’s interior. He ringed the town plaza with entrenchments, barricades, wall cannon and fortifications. The bulk of Mexican artillery was placed securely behind nearby fortifications, well sited with a clear field of fire down the broad boulevards that led to the plaza—but unable to fend off attacks that were shielded by buildings. The flat roofs of the buildings adjacent to the plaza and cathedral bristled with infantry and small calibre wall cannon.

T

witchell, Ralph Emerson. The History of the Military Occupation of New Mexico.

Smith Brooks Company, Publishers. 1909. Illustration by K. M. Chapman. At dawn, Love’s six-gun battery with accompanying ammunition caissons headed across the dusty plain towards Rosales. Through the thick cloud of dust, created by a dozen caissons and cannon being pulled by seventy-two horses. The lively strains of a bugle sounded and the detachment halted five hundred yards to the northwest of the town plaza. Then came the command, “Fire to the rear—caissons pass your pieces-trot-march—in battery.” In seeming confusion, cannon, caissons, limbers, horses, and men moved in every direction. Within a few minutes, however, the guns were unlimbered in line, the cannoneers standing at their proper posts, limbers and ammunition caissons properly aligned behind each piece.

By mutual agreement, non-combatants were afforded the opportunity to leave the town before the start of the battle. As non-combatants streamed out of the town, General Price re-positioned his troops, moving them out of the woods east of the town, and placed them so that they now surrounded the town. Lieutenant Colonel Lane’s squadron of the 3d Missouri marched to the north of Rosales. Behind Love’s battery, west of Rosales, were four companies of Colonel John Ralls’ 3d Missouri. Major Walker’s Santa Fe Battalion and two mountain howitzers covered the southern approach to the town. Major Beall’s two companies of 1st Dragoons and Captain W.L.F. McNall’s company of 3d Missouri remained in position to the east of the town.

At 10:30 a.m. General Price ordered his artillery to open the ball. Love gave the command and each of six gunners touched off their pieces. Smoke and flame belched forth as six cannon balls arched across the morning sky. In the words of Edward Glasglow, the shots struck the adobe buildings “making the mud bricks fly about pretty lively and so continued for the greater part of the day." For more than a deadly hour the American and Mexican cannon dueled one-another and two of the Mexican cannon were silenced. Upon General Price's orders, a section of the battery, consisting of a 24-pound howitzer and a six-pounder, under the command of Lt. Alexander Dyer, were shifted seven hundred yards south to the town cemetery. The remainder of Love’s battery soon joined Dyer’s two guns, now positioned less than 400 yards from the town. Despite intense counter-battery fire by Yankee cannon, a lone Mexican nine-pounder located in the plaza continued to bravely return fire. Most of its round shot flew high and did little damage to Love’s battery. Some of the overshots, however, landed amongst Colonel Ralls’ troops, killing Corp. T. Ely, wounding another trooper and killing six horses.

In the heat of battle, a nervous loader had forgot to charge his gun with a linen package of gunpowder and the rammer, unaware of this oversight, shoved a 24 pound shell down into the barrel. For want of a power charge, the gun could not be fired. Lt. Oliver Hazard Perry Taylor, commanding a nearby company of Dragoons, stepped forward and with much exertion and at great risk, removed the shell from the breach, and this allowed the piece to resume with its deadly work.

Around noon, American scouts reported that a column of 900 lancers were fast approaching and Love was ordered to fall back in order to protect the American encampment and his ammunition train. “Limber up” came the command and the cannon were hitched to the limbers and away trotted the battery to the threatened sector of the field. As it did so, rousting cheers and loud shouts of "Venceremos," “Viva Mexico,” and “Santiago” could be heard from the defenders who believed that the Yanquis were in retreat and reinforcements were arriving.

The reinforcements turned out to be nothing more than a few presidale horsemen and some unarmed campesinos from neighboring towns. Hearing the distant rumble of artillery, they came to watch the battle. These individuals skirmished briefly with a company of Santa Fe Horse and fled.

General Price decided that the lengthy artillery bombardment had not shaken the resolve of the well-entrenched defenders and that his troops must enter the town. At 3:00 in the afternoon, he ordered Lt. Love's cannon back to the cemetery with orders to provide covering fire for the impending attack. Love’s battery, under fire from two Mexican artillery pieces, trotted forward and again swung into battery.

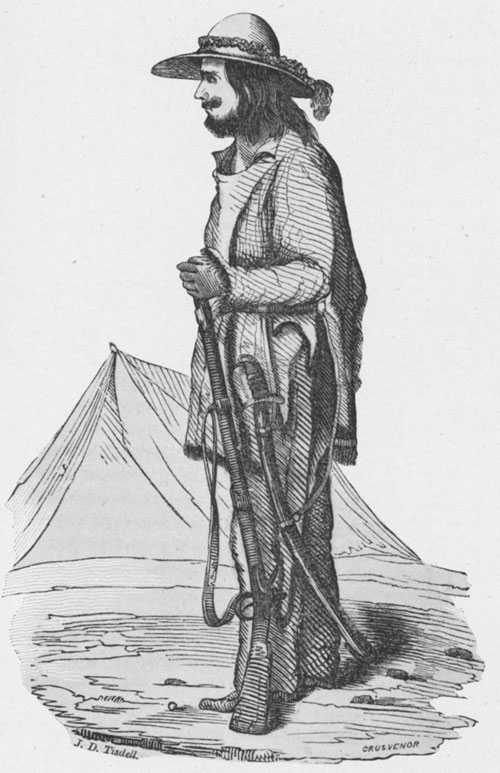

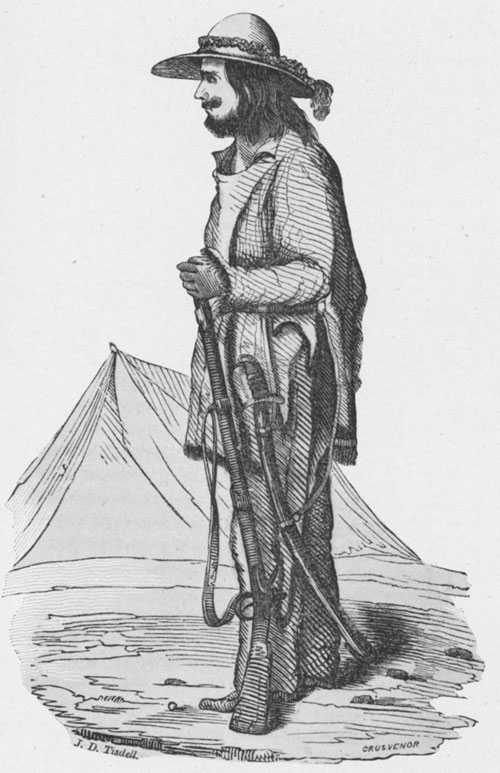

Missouri Mounted Voluinteer

Missouri Mounted VoluinteerFor the remainder of this story, please see New Mexico Historical Review, Vp;. 81, No. 4, Fall 2006.